Story highlights

Bookstores in Hong Kong are now catering to mainland Chinese tourists

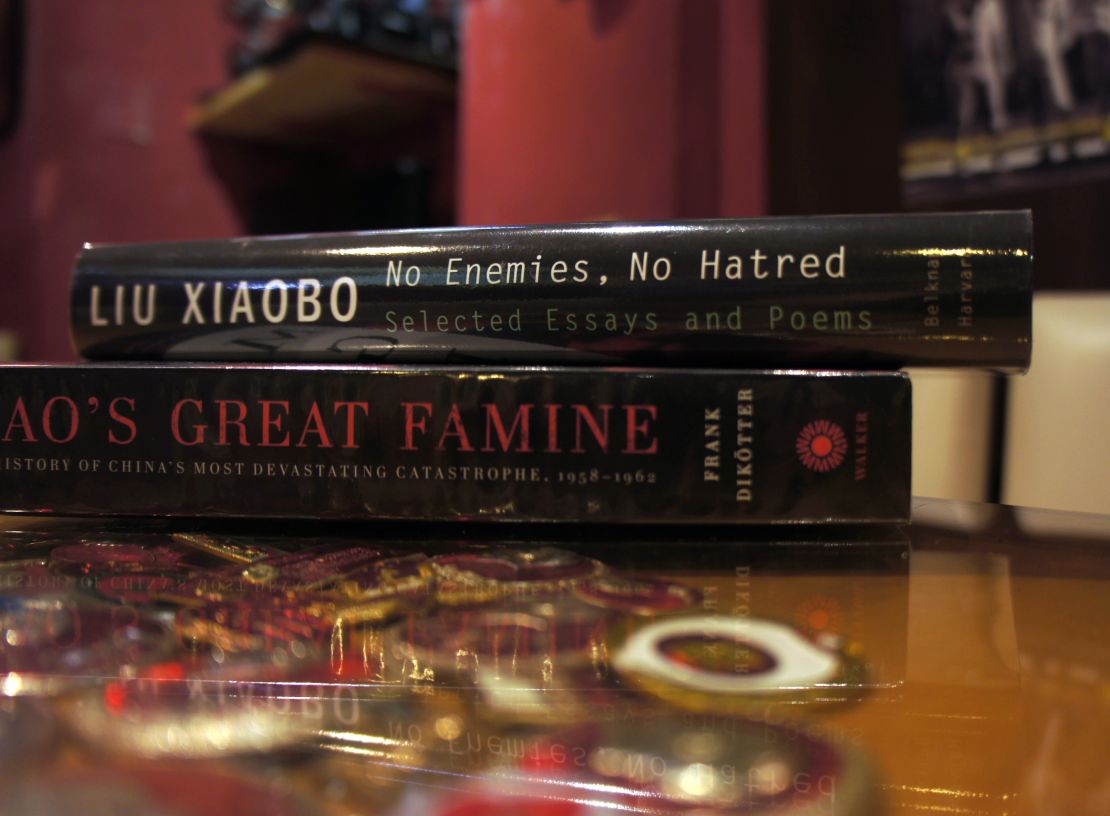

The books sell literature that is banned in China under the Communist Party rule

Topics include political scandals, history books and book about the Party itself

Experts say Chinese buy these books to feel a part of the political process

When a mainland Chinese tourist heard about a bookstore in Hong Kong that sold books banned by Beijing, he knew he had to check it out.

The Beijing native traveled to Hong Kong for a weekend in July and stopped by People’s Commune in Causeway Bay to see if the rumors were true. “I want to know the inside stories of the party,” said the man, who did not want to be identified because it was illegal to bring the books back home. “It has nothing to do with me personally but there is no way you can get those inside China.”

In mainland China the government places strict controls on mass media, which often means that political analysis and controversial accounts of Chinese history are impossible to find within the country’s borders.

However, entrepreneurs in Hong Kong – a special administrative region of China that has freedom of press – are cashing in on the ban to cater to the millions of mainland Chinese who travel to Hong Kong to shop.

Bookstores such as People’s Commune stock their shelves with forbidden tales of everything from the Tiananmen Square crackdown of 1989 to the ongoing scandal of ousted Communist Party official Bo Xilai.

Deng Zi Qiang, the owner of People’s Commune, has seen a growing flood of mainland Chinese customers since he opened the store in 2003, the same year Hong Kong was opened to an increasing number of independent travelers from China. In 2011, Hong Kong had 28.1 million visitors from the mainland, compared to 13.6 million in 2006, according to statistics from the Hong Kong Tourism Board.

Now, “95% of the customers are from mainland China,” said Deng, a Hong Kong native.

The People’s Commune has opened an account on China’s microblogging site Sina Weibo to inform their Chinese customers of new selections and to take orders. Most buyers are from developed cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, Deng said. They range in age from 30 to 40 years old and are scholars or businessmen.

Even Chinese government officials and police chiefs have come through his doors. “Some of them show me their police IDs when checking out” to prove they are government officials, Deng said.

As a businessman, Deng said he doesn’t care too much about political rumors and scandal, but his book selection taps a huge potential market.

“Mainland China is short of information and freedom of expression compared to Hong Kong,” Deng said. “Besides luxury goods, I thought it could also be an attraction for mainland Chinese.”

He said that he sells between 200 and 300 books a month.

Zhou Baosong, a political professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said part of the allure for mainland Chinese is that reading such books makes people feel like they are political participants, rather than just helpless observers.

That also explains why many Hong Kong locals don’t pay much attention to the bookstores.

In democratic societies like Hong Kong people don’t exhibit the same passion for reading political books since they have adequate ways to get information and be involved in politics, Zhou said.

But this information climate also provides lots of room for rumors and falsehoods.

“Mainland Chinese are more keen to read (whatever they can),” said Zhou. “Rumors then get the opportunity to spread.”

On a recent Friday night dozens of customers sat in the store browsing selections at People’s Commune.

“I found some books ridiculous,” said a stock broker from Fujian Province, in Eastern China, who stopped in the bookstore while his wife and daughter shopped nearby. “I think our country is the best place to be.”

When returning to China, his customers risk having them confiscated at customs, Deng said. Still, many make repeated trips to obtain the books, he added.

But it’s not a defiance of the Communist Party that fuels his desire to read these books, said the customer from Beijing.

“Just because I’m reading these books, doesn’t mean I’m anti-Party,” he said. “In fact, if the people have more access to the decision-making process they can give suggestions and provide their wisdom.

“As long as it doesn’t hurt the fundamental well being of its people, I don’t see a reason for the country to ban the information,” adds the man, who left with several political magazines in tow. “After all, we want the country to be better and our lives to be improved.”