Editor’s Note: Anthony H. Cordesman holds the Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Follow CSIS on Twitter.

Story highlights

Anthony Cordesman: None of Syria's problems can be solved until its civil war is solved

Cordesman: The U.S. must be involved for both humanitarian reasons and self-interest

He says at the same time, the U.S. must carefully ration its aid and resources to the region

Cordesman: Sadly, Syria is just this month's crisis in a region full of complicated conflicts

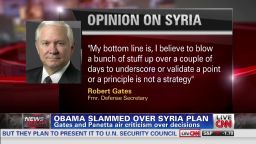

It is time to stop focusing on the next month and start focusing on the years to come. Syria is not a chemical weapons crisis any more than a country whose problems can be solved by supporting the rebels.

Like many of the countries in the Middle East – Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Tunisia and Yemen – it has already been destabilized by a mixture of population pressures, weak economic development, authoritarianism, corruption, failed governance, and deep ethnic and sectarian divisions. It will take years for them to achieve stability and move along some path toward growth and development.

Getting rid of Bashar al-Assad’s chemical weapons will be a major challenge. Al-Assad is likely to resist, and delay. An ongoing civil war is scarcely the ideal environment for a complex nationwide effort in arms control. Russia is likely to put al-Assad’s survival before pushing Syria toward full compliance and to oppose any use of force.

The November deadlines for even initial compliance are politically and militarily necessary, but may not be workable in practice. Destroying, neutralizing and moving all the weapons is a task of unknown scale and difficulty with no resources now in place.

Reports that Syrian officials have turned over materials to prove the August 21 chemical attack was carried out by the rebels only further complicates matters. Added to that, the return of U.N. chemical inspectors to Syria in the coming days means that attempts to coordinate the task of disarmament will be further delayed.

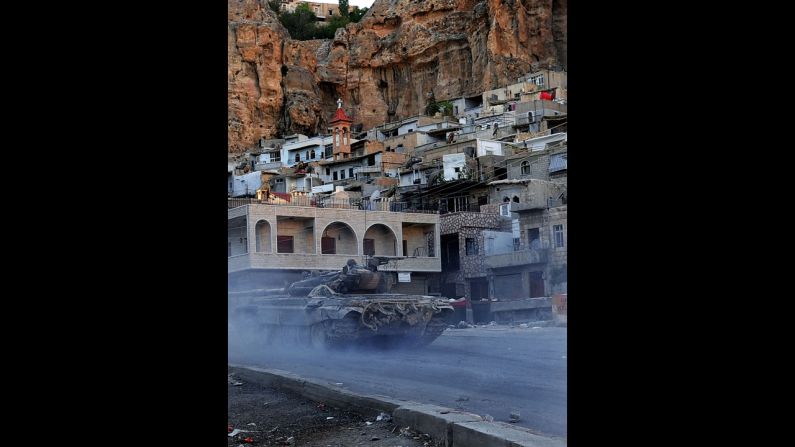

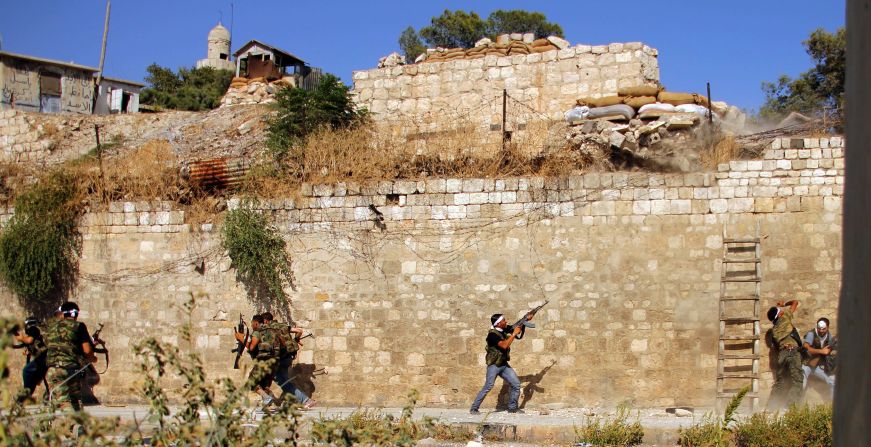

These developments aside, what is more important is the fact that any effort to deal with Syria’s chemical weapons does not have any clear impact on a civil war that has almost certainly killed 120,000 Syrian civilians, driven some 2 million out of the country, and displaced well over 4 million.

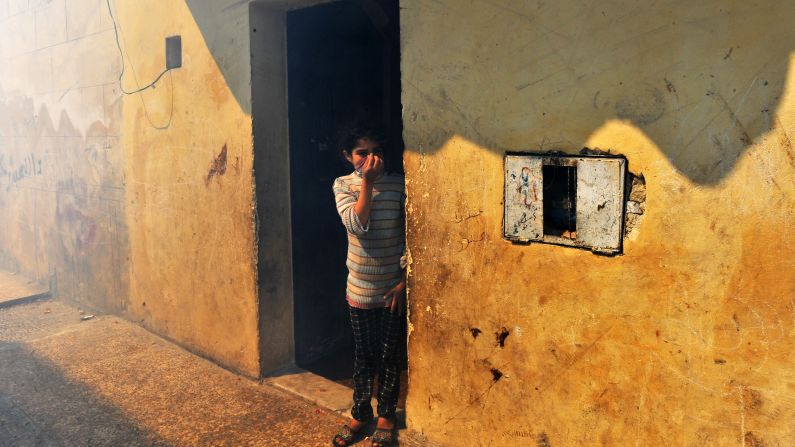

Syria’s economy is crippled, with high levels of youth unemployment and underemployment. Some 20% of the population has lost a home, a job, or a business. Education is badly disrupted in a country where one-third of the population is 14 years old or younger. Medical services and every other aspect of social and physical infrastructure have been badly damaged.

None of these problems can be solved until the civil war is solved, and it cannot be solved by partition, which would divide the country into unworkable economic zones based on religion, ethnicity, anger or hatred.

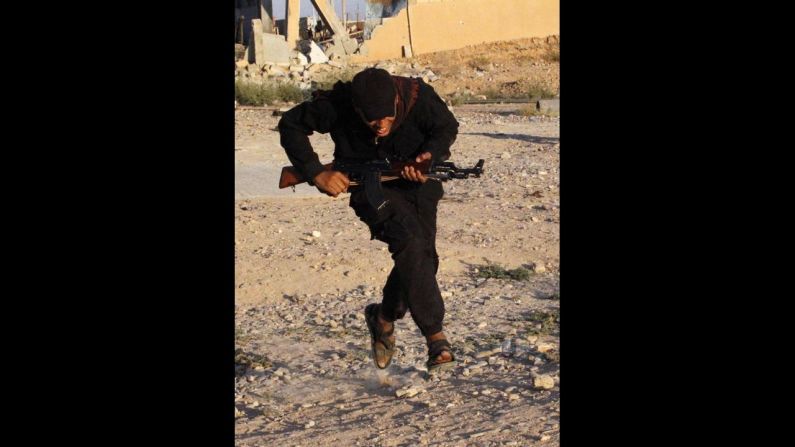

An al-Assad victory would leave a seething majority of Sunnis under a dictator who could only survive by using repression at the cost of recovery, development, human rights and freedom. A rebel victory could deprive Alawites and minorities of their rights and bring Islamist extremists to power who would most likely repress the nation’s moderate Sunni majority.

The United States cannot solve any of these issues from the outside. It can push for the full destruction of the chemical arsenal and an end to the far more lethal use of conventional force against civilians. It can counter the aid to Assad from Iran and Russia by providing arms and training to the moderate parts of the rebel forces. It can push for negotiations that will put a moderate unity government in place. It can continue to provide humanitarian aid, and if a stable government does emerge, it can aid in the process of recovery and development that will take years.

In practice, the United States must pursue this course over the years for both humanitarian reasons and self-interest. A violent, polarized Syria is a breeding ground for extremism and terrorism. It threatens allies like Israel, Jordan and Turkey. It is worsening the divisions and violence in Lebanon and Iraq, and giving Iran a major new zone of influence and growing ability to threaten our Arab allies in the Gulf and the world’s oil exports.

At the same time, however, the U.S. must carefully ration its aid and military resources. Syria is not as important as the crisis in Egypt or Iraq. Iran is much more of a direct threat. Yemen and Iraq are both far more of a center for al Qaeda than Afghanistan and Pakistan. Bahrain is a key ally and the center of our naval operations in the region. Tunisia needs help in becoming a real and stable democracy. Morocco and Jordan are allies that also need aid, and Israel’s security is a constant concern.

In short, Syria is just this month’s crisis in a region where the Arab Spring has become at least a decade of violence, religious conflict, threat to development and progress, and where the United States can neither solve a single problem quickly nor take a single risk of disengaging from an effort to help.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Anthony Cordesman.