He slept on a friend’s couch, hustled for odd jobs and hitchhiked along the campaign trail.

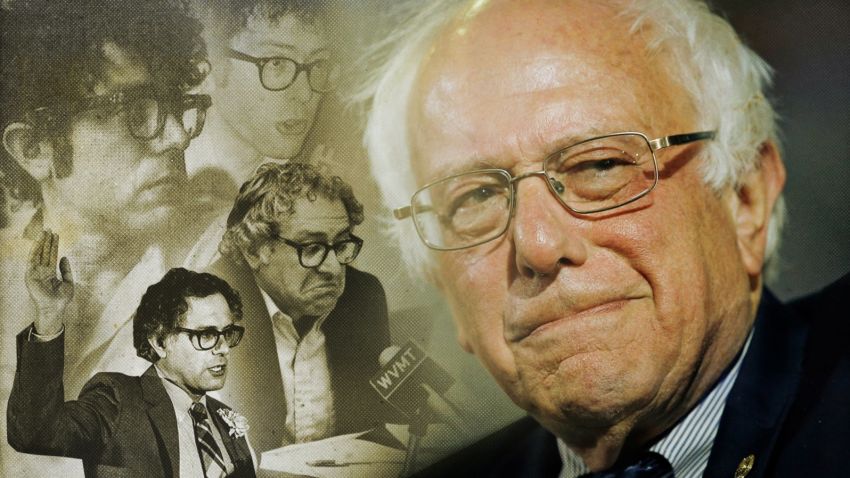

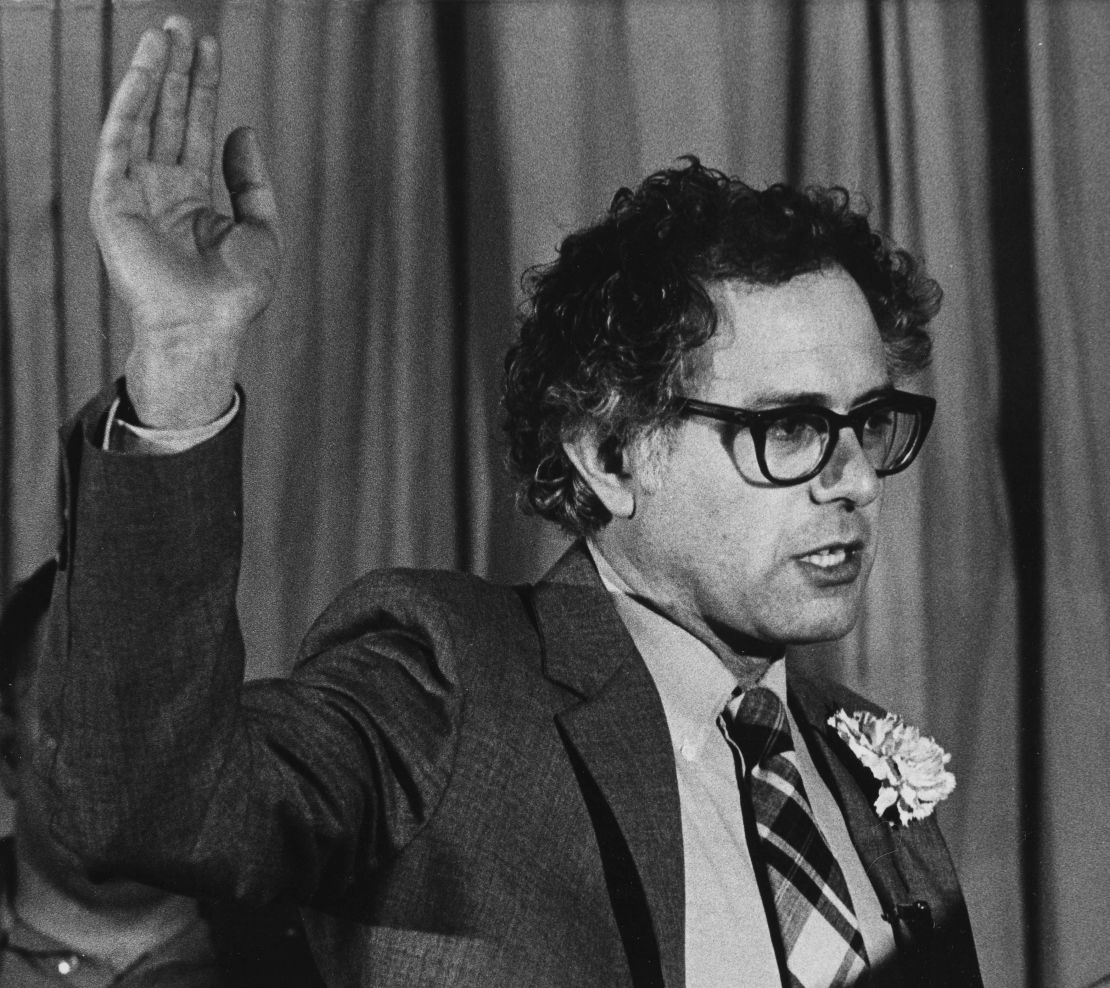

In the 1970s, Bernie Sanders, then in his 30s, ran – over and over again in Vermont – and lost repeatedly, never cracking double digits. In a series of quixotic bids at statewide office as a member of the self-described “radical” Liberty Union Party, he railed against corporate titans and promised to eliminate laws regulating drugs, homosexuality and, before the Supreme Court stepped in, abortion.

He campaigned in a local prison and spoke forcefully about racial disparities in the criminal justice system. The government, he said during a talk about desegregation busing, “doesn’t give a sh** about black people.”

Unlike so many other public figures with long careers or winding arcs, Sanders did not arrive at this moment of national reckoning through a personal or political “evolution.” He broke through, instead, with an uncompromising, insistent vision of radical upheaval – and a taste for conflict with the forces determined to keep him on the fringes.

The consistency of Sanders’ message over time has become a cornerstone of his presidential pitch. This account, which spans parts of seven years in the 1970s, was drawn from a CNN KFile review of thousands of pages of archived Liberty Union Party files and newspaper articles newly available online, as well as interviews with longtime acquaintances and onlookers.

Many of the speeches, editorials and interviews featured here are nearly indistinguishable from what Sanders might have said just the other day, out on the presidential hustings, although the sharper edges of his message have slightly softened over time. He is still fighting, as the 2020 primaries near, many of the same battles he first joined during his early campaigns as a member of the Liberty Union Party in the 1970s.

The stage now is much bigger and the stakes, in the second half of Donald Trump’s presidency, are astronomically higher, but Sanders is still telling the same story – of a country coming apart at the seams, in desperate need of political revolution.

Sanders would run for office in Vermont four times as a member of Liberty Union, from 1972 to 1977.

He then left the party, frustrated by its inability to crack the locks of power. But these were not wilderness years. The ’70s, for Sanders, were an education. He began the decade as a political neophyte with no ties to his new home state. A New York-born and Chicago-educated activist in search of new politics, he would emerge as one of the most well-known progressive political figures in Vermont.

In 1981, just shy of his 40th birthday, he would leverage that reputation into a successful run for mayor of Burlington. Sanders then was elected to the US House in 1990 and the Senate in 2006.

“What you see is what you get. What you see is what you’ve always got,” said John Franco, who ran for office in 1974 and 1976 under the Liberty Union banner and worked in his administration when Sanders became mayor of Burlington.

“We used to call this his standard speech – we call it the ‘yellow legal pad speech’ because he would write it on a yellow legal pad and he would give, it would be the same goddamn speech he’d given 400 times in the past!” Franco said. “It’s been the same speech. I cannot watch him in debates anymore. I won’t watch him in debates. I’ve heard it all before a thousand times.”

Old enemies foreshadow new ones

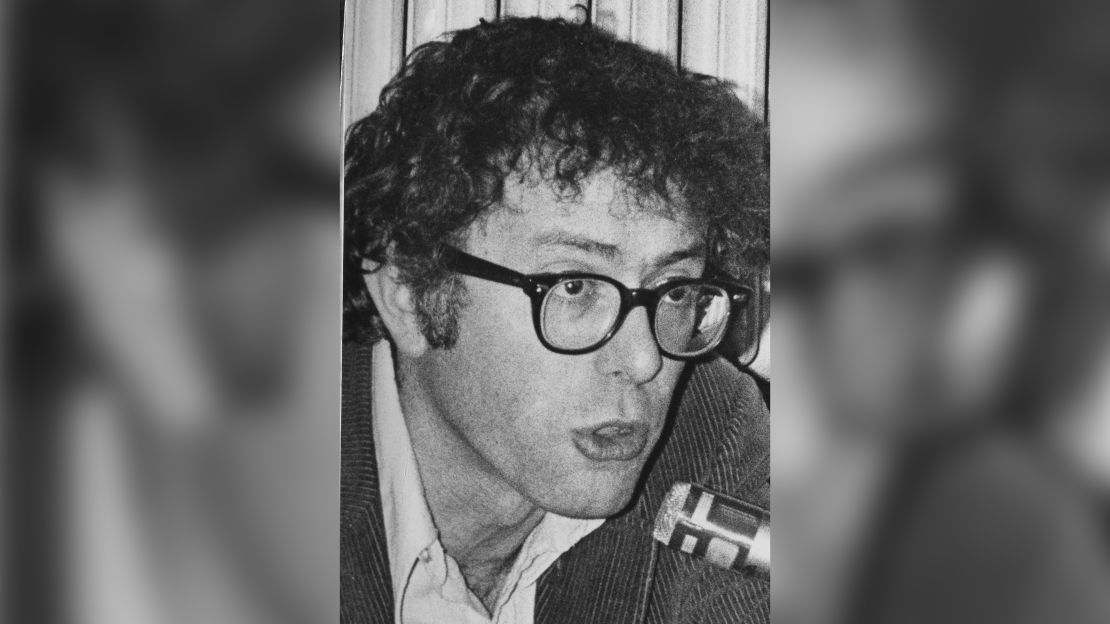

It was October 1973 and Sanders was giving a talk on the radio.

“There are two worlds in America – and two worlds here in the state of Vermont,” he said. “One of those worlds is the world of Richard Nixon, and the millionaires and billionaires he represents. This is the world of the 2% of the population that owns one-third of the personally held wealth in America.”

Now, in 2019, Sanders wrote in a recent column: “Today, while hundreds of thousands of bright young people cannot afford to go to college and millions are struggling with high levels of student debt, the top 1 percent owns more wealth than the bottom 92 percent.”

The message remains basically the same, only the numbers and the characters have changed. Nixon has given way to Trump, and the Koch Brothers, a favorite target in this decade, have replaced the Rockefellers.

When President Gerald Ford selected former New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller to be his vice president, Sanders lashed out at the decision, calling it a “tragedy for the nation” and “an insult to every working person in the country.” The Rockefeller fortune, he said, represented “a dangerous threat to the economic and political well-being of America.”

“America is supposed to be a democracy, not an oligarchy. Our leaders are supposed to come from the ranks of the people and represent the needs of the people,” Sanders said. But what to do?

“We should begin the task of dismantling their economic empire,” he continued, “and developing an economy which will produce wealth for all the people, and not for the privileged few.”

In his current campaign for the presidency, Sanders is attempting to strike a delicate balance between blistering criticism of Trump – whom he routinely calls a racist and pathological liar – while trying to claw back for the left a swath of working class white voters who opted for the President’s right-wing populism in 2016.

Sanders demonstrated an ability to win them over in Vermont, whose population was 94.5% white, according to the most recent census, and, in a prescient essay from the second issue of Movement, a small magazine put out by Liberty Union that he published and edited, wrote about the resentment of those voters and the danger presented by a politician who could tap into it.

His subject in 1972 was George Wallace, the former segregationist and governor of Alabama, who won nearly 10 million votes in the 1968 general election.

In interviews with Wallace supporters, Sanders said he found “a certain feeling of admiration and respect for” their anger at the political system but feared that, with Wallace’s influence growing, their collective rage posed an existential threat to civil rights and American pluralism.

“I came away from these Wallace interviews with two basic feelings. First, that democracy in America (in any sense of the word) just might not make it,” Sanders wrote. “My mind flashed to scenes of Germany in the late 1920’s. Confusion, rebellion, frustration, economic instability, a wounded national pride, ineffectual political leadership – and the desire for a strong man who would do something, who would bring order out of the chaos.”

“Could it happen here?” Sanders asked, “With the inability of the national leadership to solve the real problems facing this country, could the blacks, long-hairs, ‘welfare chiselers,’ and political dissidents become the Jews and Communists of the Nazi experience? Could it happen here? I see no reason why it couldn’t.”

Sanders in more recent campaign speeches has accused Trump of playing similar notes by stoking anger and weaponizing racism during a time of social unrest.

“This President is the first President in the modern history of our country who is trying to divide our people up based on the color of their skin, the country they were born in, their sexual orientation, their gender, their religion,” he said at a CNN town hall in February.

How radical?

Campaigning in 2019, Sanders rarely looks back beyond the 2016 election.

The ideas he ran on then, he’s fond of recalling, were deemed “too radical” by mainstream Democrats and the political media.

But then, Sanders likes to say, “a funny thing happened” and only three years later, here he stands - in Iowa, in New Hampshire, California and South Carolina, New York and Chicago – among the front-runners for the party’s presidential nomination and one of the most influential politicians in America.

Sanders knows how quickly social and political norms can change.

The 1971-1972 Liberty Union platform called for eliminating all laws related to abortions, drugs, homosexual relationships and birth control. It arrived two years before Roe v. Wade and just after New York City’s Stonewall Riots – when police raided a gay bar in Greenwich Village and set off protests now widely viewed as a catalyst for the modern LGBT rights movement. At the time, every state but two had anti-sodomy laws on their books.

“It strikes me as incredible that politicians think that they have the right to tell a woman what she can or cannot do with her body,” Sanders said in 1972. “This is especially true in Vermont, where we have a legislature which is almost completely dominated by men.”

The party platform introduced Sanders as a conscientious objector who refused to join the military during the still-ongoing Vietnam War and announced Liberty Union’s support for women and the black liberation movement, citing the “deep and abiding racial and sexual discrimination” in American life. The relentless bombing of Vietnam, Sanders said at the time, was an “atrocity.” After anti-war veterans temporarily seized control of the Statue of Liberty in protest, he sent them a telegram congratulating their “courageous act.”

Speaking outside a prison where he campaigned in 1972, Sanders blasted a criminal justice system that disproportionately locked up minorities.

“It says a great deal about our country that the richer our country gets, the more of us there are behind prison bars and that an overwhelming number of those who are in jail are poor, nonwhites,” Sanders said.

On the politically charged topic of desegregation busing, Sanders expressed concerns about the program’s unintended consequences.

The Middlebury College campus newspaper reported in 1974 that Sanders believed busing – “(doing) bad in the guise of good things,” as he put it – risked creating racial hostility where none previously existed.

“The government,” he said, “doesn’t give a sh** about black people.”

‘Why doesn’t television reflect the real suffering and misery of life?’

In the second decade of the 21st century, Sanders has emerged as one of the most powerful single enemies of – and some would argue threat to – corporate America’s influence on the wheels and gears of its political institutions.

The language he uses now, bird-dogging Amazon and Disney, is remarkably unchanged from the mid-1970s, when he accused companies of “blackmail” for seeking out tax incentives in exchange for keeping their businesses at home.

Sanders promised radical measures aimed at the pocketbooks of companies that relocated from Vermont in search of more profitable pastures.

“If the banks and corporations feel that they can better exploit the people of Mississippi, New Hampshire, Hong Kong or Puerto Rico in order to make their blood profits – let them go there,” Sanders said, announcing his 1976 campaign for governor. “In the Dominican Republic, American companies pay native workers $2 a day for a full day’s work. Vermont is not going to compete with that kind of slavery.”

Sanders, in a Valley Voice story about the campaign, is quoted saying that corporations are playing one state off against the other to get the best deal. Those companies, he added, that flee Vermont for lower-wage areas should be hit with stiff penalties, including a requirement to pay the workers they left behind two years’ salary and a decade of taxes to the local government.

This punitive approach to outsourcing has echoed down the years.

In November 2016, Sanders wrote a Medium post criticizing United Technologies, a major government contractor, for proposing to relocate manufacturing plants to Mexico. He called for the company to repay “tax breaks and other corporate welfare” it had received and to deny its executives bonuses, golden parachutes and stock options “for outsourcing jobs to low wage countries.”

Despite his commitment to democratic socialism, Sanders rarely – and even then, only with some arm-bending – engages on the nuts and bolts of the ideology that has guided him for so long. That too is a constant dating back decades.

Jim Rader, his friend since the 1960s, says that Sanders has always focused on concrete steps and what he could do in the present.

“He does feel that way” about corporations and economic disparities, Rader said. “And he always does.”

But in a long interview uncovered by CNN, Sanders in 1976 spoke with the Vermont Cynic, the University of Vermont student newspaper, in more philosophical, sometime spiritual terms about what he viewed as harsh remainders of consumer-driven life under an increasingly hyper-capitalist society.

“It’s quite obvious why kids are going to turn to drugs to get the hell out of a disgusting system or sit in front of a TV set for 60 hours a week,” Sanders said. “What we’re saying is that people have got to begin working with and for other people, and I think that’s an extremely strong motivating factor why young people should vote for us.”

And while he doesn’t often get into soul-searching or sociological discussions in 2019, Sanders on the trail has spoken often about what he describes as a debilitating sense of futility that has enveloped life in parts of rural and post-industrial America – particularly areas that voted heavily for Trump. The opioid epidemic, among others, he says, is one of a number of “diseases of despair” threatening the country.

His criticism of the media in the ’70s also sounded very much like it does today. In an interview last October, CNN asked Sanders how he planned to compete with headline generators like Trump going forward.

“I made news today. I made big news today,” Sanders said, frustrated by the question but eager to deliver his take. “Because I talked with four senior citizens, you were there, and one senior said that the cost of her medicine soared. Extraordinary news. Because that’s news that millions of people will shake their heads at. What you mean by news is I gotta say something that I didn’t say yesterday.”

That was 2018. At an event in 1974, Sanders asked the audience: “Why doesn’t television reflect the real suffering and misery of life?”

In and out of the mainstream

Sanders’ worldview, colored by a swirl of empathy and ideology, is locked in. But his politics – and the language he uses to promote them – have become more polished and, on some occasions, less radical than during his first decade in Vermont.

He has also since rejected a number of positions he and the party advocated for during the time, campaign communications director Arianna Jones confirmed to CNN.

The push, in 1972, by Movement magazine to lower the voting age to 14 from 18 has long been discarded. Sanders no longer supports, as mentioned in the same issue, a “need to abolish compulsory education (and, perhaps, schools) so that kids can grow up with a sense of independence and strength rather than as cogs in this great bureaucratic, oppressive morass which is called America.”

Four years later, in his interview with the Cynic, Sanders lamented the state of American society while casting in a more forgiving light Cuba and China, which was in the final year of the Cultural Revolution.

“What we’re saying is that we’ve got to unleash the energy that exists in people to start doing meaningful things,” Sanders told the paper. “Contrast what the young people in China and Cuba are doing for themselves and for their country compared to the young people in America.”

Sanders has long since distanced himself from the deadly excesses of the communists dictatorships of the era. He has also dropped old calls to nationalize certain private industries and legalize all drugs, including heroin.

“I’m not saying drug use isn’t a definite problem, but making drugs illegal isn’t helping solve anything,” he told the Bennington Banner newspaper in 1971. “If heroin were legal, at least we’d know the dimensions of the problem, and be able to deal with it rationally.”

Sanders can appear uncomfortable when asked about those positions today. In a CNN town hall, he bristled when anchor Chris Cuomo brought up his past support for government seizures of major American industries.

“When did I say that?” Sanders asked.

“In the ’70s,” Cuomo responded, before Sanders sarcastically replied, “OK, right.”

On other points, Sanders has simply rolled back or effectively ignored his bygone dreams of a more aggressive socialist reformation.

CNN’s KFile previously reported that Sanders had argued for nationalization of the energy companies and the public ownership of banks, telephone, electric, and drug businesses, along with the major means of production, such as factories and other capital producers. During his 1974 Senate run, Sanders said one plan to expand government included making it illegal to gain more wealth than a person could spend in a lifetime and having a 100% tax on incomes above this level. (Sanders defined this as $1 million annually, equivalent to about $5 million today).

“No fundamental change can come about in the country until the wealth and power are broken up and the people themselves direct the economy and government,” Sanders said in a 1976 interview with The Valley Voice.

In a gubernatorial debate that year, audio of which KFile obtained from the Vermont Historical Society, Sanders said the economy would need to be publicly owned and controlled.

“In the long run, what has got to happen on the national level and on the state level is the people of this state and country have got to stand up to the 2 or 3% of the population that controls the economy,” Sanders said. “And the billions and billions and billions of dollars owned and controlled by these people have got to come within the public domain.”

His policies were particularly punitive toward corporations and their investors.

Sanders suggested a plan to bankrupt the state’s utility companies by drastically reducing their rates, thus allowing the state to swoop in and purchase their infrastructure at rock-bottom prices. At one point, he called for seizing the utilities without compensating the banks or stockholders.

Apart from his electoral campaigns with Liberty Union, Sanders launched a widely reported boycott of the state’s telephone company after it proposed increasing rates by 38%. When the company’s general manager complained that it was “going broke” without the hike, Sanders taunted them with a donation: one dollar, which was eventually returned. Despite his frosty relationship with the state’s newspapers, the Brattleboro Reformer published an editorial praising Sanders for his work opposing the new charges.

Sanders would, in a statement announcing his 1976 gubernatorial bid, call for the public takeover of Vermont’s telephone company, which he called “probably the single greatest rip-off company in America,” and a moratorium on debt payments to New York City banks. He also pledged, according to an article in The Valley Voice, that if elected governor he would pursue legislation allowing the state to direct Vermont-based banks to invest their deposits in low-income housing construction.

“There is $2 billion in Vermont banks at the present moment, and the only people who determine how that money is invested are the director of banks,” Sanders said in an interview with the Voice that year. “The state and the depositors have a right to direct where that money should be invested.”

The ‘sacrificial lamb’

Sanders’ initiation into electoral politics - and all the scrums that forged his public persona – began with a quiet invitation from an old friend.

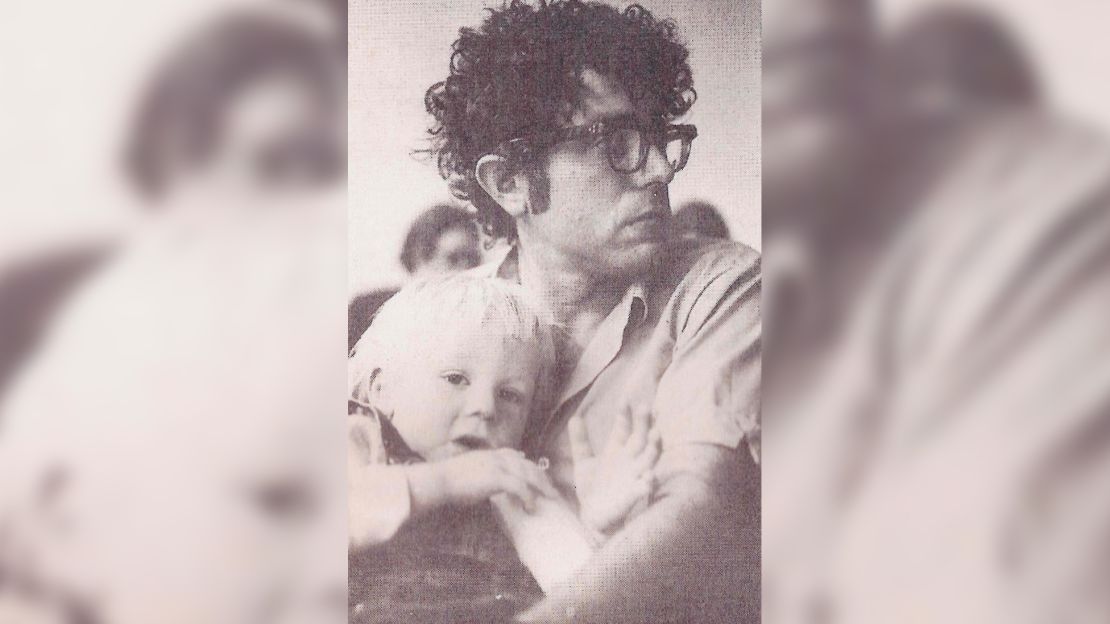

In 1971, Sanders, having just turned 30, was working on-and-off as a carpenter and sleeping on the couch of his friend Jim Rader, a casual Liberty Union supporter.

One day, Rader says he asked Sanders to a party meeting at Goddard College. Attendees described it as a small gathering, maybe a couple dozen people in the room. Peter Diamondstone and Doris Lake, the husband-and-wife party co-founders, led the proceedings, which quickly turned to a discussion about the next year’s Senate race.

An incumbent senator had died and the party was looking to recruit someone – anyone – for a long-shot special election contest.

“I see this tousled-headed, rumpled individual, and I said, ‘Hey you,’ ” John Bloch, a cousin of Diamondstone’s, recalled of his first encounter with Sanders. “I ain’t even know his name.”

“I said we haven’t got a chance in hell of winning this, but will you be the sacrificial lamb?”

Most members of the party at the time were young adults who couldn’t afford to dedicate time to a political campaign for a party with little to no funding or campaign structure.

So Sanders volunteered.

“We were just hysterical laughing about this,” said Rader, who drove Sanders home after the meeting. “It was an exciting novelty that he had the chutzpah to jump in there.”

Sanders was an unconventional candidate running on an unconventional platform. He wanted to legalize hitchhiking, which, as it happened, was often a mode of travel he used to cover the state during a campaign that would ultimately yield him 2.2% of the vote.

His next five years with the party would be marked by greater success in organizing communities and developing a personal reputation around the state as its leading progressive activist. But Sanders’ electoral tallies increased only marginally. After dipping to 1.1% in the 1972 gubernatorial election, he secured 4.1% of the vote in the 1974 Senate election and just surpassed 6% in the 1976 governor’s race.

The votes weren’t there. But Sanders’ prominence – and reputation as a gruff insurgent – was growing.

At one 1976 event, reported on by the Burlington Free Press, Sanders, speaking to an audience of 300 teenagers and their parents with other candidates for governor, turned to the Democratic candidate, Stella Hackel, and reintroduced her as “a very intelligent person and a good lawyer who once worked very hard to raise your parents’ phone bills.” The crowd booed and, in recounting the exchange, the Burlington Free Press likened the scene to “a party where a drunken guest, for no apparent reason, has just insulted the host.”

Sanders continued his inflammatory speech, refusing to tone it down for the young audience.

“The Liberty Union demands you do more thinking,” he said, unbothered by the hostile reception. “We want you to see if what your books tell you and what your teachers tell you and what Walter Cronkite tells you may not be the whole truth.”

“What people want you to be is good little boys,” Sanders said. “It’s time that you stop being good little boys.”

Outside of his campaign activities, Sanders has remained active in the state’s progressive counterculture.

Movement – the Liberty Union magazine – was his megaphone and he used it to comment on contemporary economic and social issues. In a 1972 article titled “Natural Childbirth in a Vermont Commune,” he described witnessing a woman named Lorraine give birth in a home communal setting - and used the scene to criticize the institutional approach to hospital care for women.

In an interview with the new mother, Sanders posed a series of intimate questions that might make mainstream society blush.

“Did you tear?” he asked. No, Lorraine said, before discussing her decision to eat the afterbirth. Sanders continued: “How long after the birth did you eat the afterbirth?”

Lorraine answered the questions matter-of-factly (about an hour later, she said), describing how the process worked.

Leaving Liberty Union

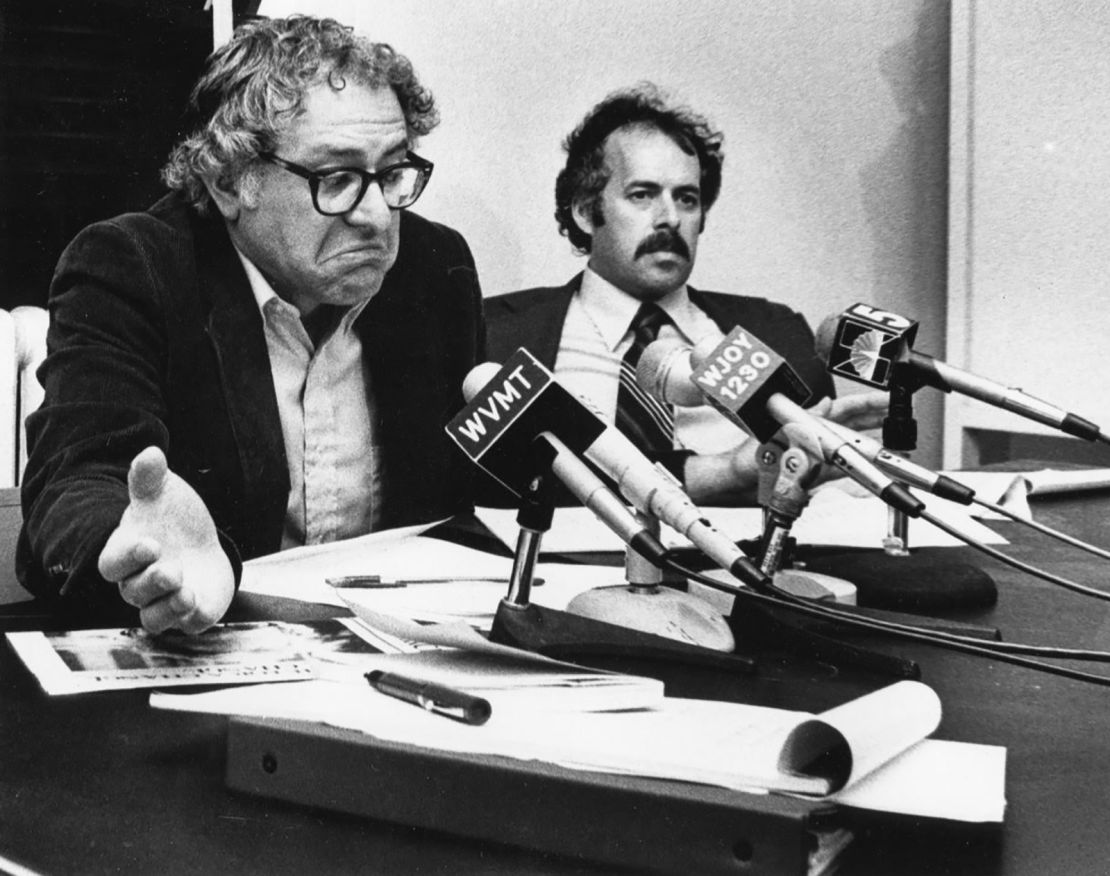

Sanders resigned from the Liberty Union Party in 1977, the Burlington Free Press reported, telling the paper that “a serious political party cannot maintain the respect of people if it simply pops up every two years for elections.”

“Where is the Liberty Union right now?” Sanders asked a reporter sarcastically that year. “If you find it, you tell me.”

The Burlington Free Press described the party’s inability to attract more working class voters, internal dissent over its material goals and lack of a year-round political machine as the main drivers of its thwarted ambitions.

Other members, though, spoke of the immense personal and financial toll it took to run such a party with no major financial backing. Without money or success at the polls, the sacrifices were beginning to pile up. The payoffs were not.

“Virtually everybody in the Liberty Union is working extremely hard trying to maintain body and soul,” Sanders said at the time. He also began to fall out with Diamondstone and Lake, who prioritized the movement – and its work to shift the dynamics of the political scene – over successes at the ballot.

“It’s funny, the little things that stick in my head,” Lake said, describing a birthday party Sanders had after he left Liberty Union.

He hadn’t yet been elected mayor of Burlington. That came in March 1981. But his trajectory was clear.

“It’s so trivial,” Lake said, “but somebody gave him some ties and shirts and there was some joking about it. You know, like, like now you’re really, gone traditional.”