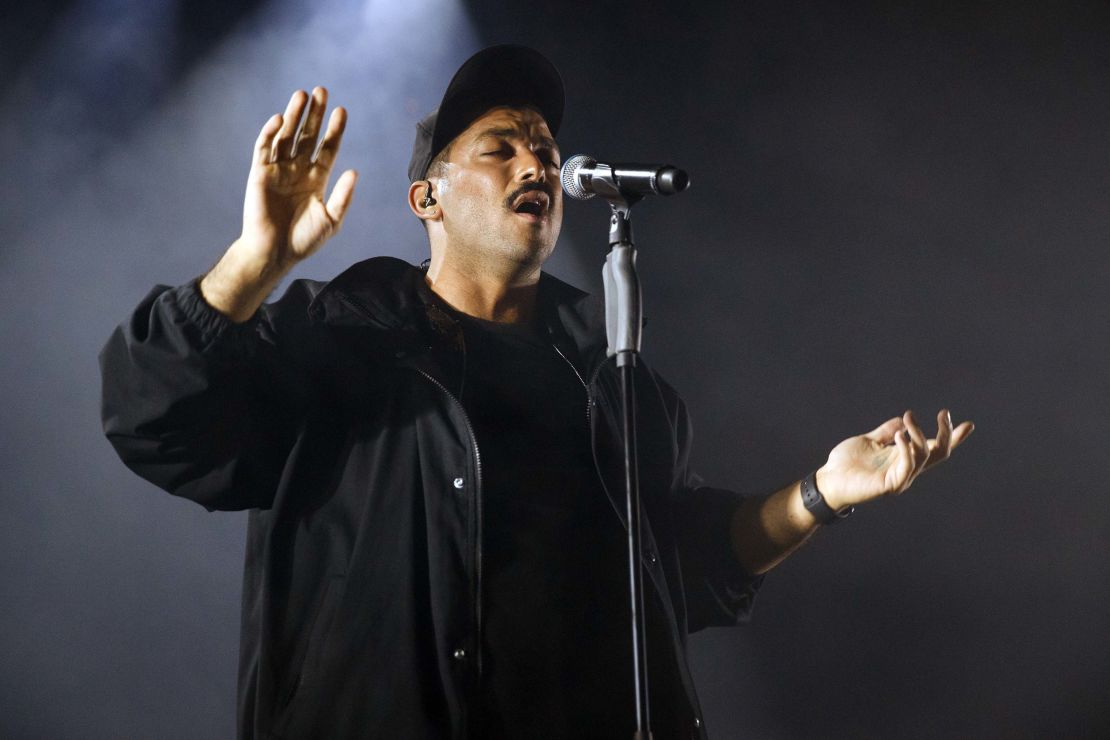

Hamed Sinno, then 22, was on stage for Mashrou’ Leila’s first major concert. The frontman of the genre-busting band danced in circles, hands in the air, and then looked intently at violinist Haig Papazian. Papazian began to play the first notes of the group’s breakthrough hit, “Raqsit Leila” (the dance of Leila).

The crowd was euphoric. Many in the audience had known music act Mashrou’ Leila from the band’s earliest days, performing in small local festivals around Lebanon. Their bold lyrics about queer romance, political corruption and religious sectarianism sung to the Balkan-influenced tunes and Sinno’s soaring vocals.

Mid-song, Sinno paused. He signaled to an audience member to hand him a rolled-up piece of fabric. As he leapt around the stage, Sinno, who identifies as gay, unfurled the gay pride flag to rapturous applause.

“That was a moment of history,” recalled one Lebanese activist, who identifies as queer and attended the show at the 2010 Byblos International Festival but who declined to be named for security reasons. “Hamed carried it like (late Egyptian diva) Umm Kulthum carried her white scarf and sang.”

This was likely the first time the rainbow flag had appeared on a major Lebanese stage. Prime Minister Saad Hariri was in the audience as Sinno sang about political corruption and police violence.

“It felt like justice,” said the activist.

Mashrou’ Leila had been slated to perform at the Byblos Festival for their third appearance at the festival over the years on August 9, 2019. This followed a rapid rise to relative global fame with the group having performed at prominent venues, such as the Barbican Centre in London and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as multiple international Lebanese festivals.

But this time, the Byblos concert faced threats of a violent shutdown. Right-wing Lebanese Christian activists, who accused the band of “blasphemy,” vowed to stop the performance “with force,” unleashing a virulent social media campaign against the group.

Highlighting lyrics that they interpreted as “devil worship,” some activists invoked the crusades. Another Facebook group called the “Soldiers of the Lord” tried to rally priests and politicians to join their bid to stop the concert.

Eventually, the Maronite Catholic Eparchy of Byblos also demanded the concert be canceled, citing a violation of “religious values.”

A range of allegations against members of the band swirled. The band said their members were questioned by police. State media reported that members of the band were investigated for offending “Christian sanctities” and then released. The band’s lawyer said they face no criminal charges.

Still, festival organizers caved to the wishes of right-wing Christian activists and scrapped the performance, saying it was canceled to “prevent bloodshed.” Church leaders and right-wing activists hailed the move as a “victory.” But for the people who felt redeemed by the band’s 2010 concert, a sense of desperation set in.

Lebanon’s rights activists had been making a series of small gains in recent years in women’s rights, LGBT freedoms and others. But now it seemed that the tide was quickly changing.

“I felt frustrated. I felt a kind of helplessness,” said the unnamed activist. “At the same time, I felt it was surreal.”

Post-truth in Lebanon

For some, the case of Mashrou’ Leila has marked the start of a post-truth era in Lebanon. The controversy largely comes down to a dispute about the meaning of song lyrics.

“Nobody is asking for the truth. Everyone is expressing his hate and that’s why the band was a victim of lots of falsifications and fake news,” said human rights lawyer Nizar Saghieh, who is part of the legal team advising the band on how to navigate the scandal.

“It’s not the first time that an artist is accused of blasphemy (in Lebanon),” said Saghieh. “But it is the first time that the artist is accused and given a verdict in a mob trial against them.”

In a statement Wednesday that followed the cancellation, Mashrou’ Leila said the songs at the center of the controversy were subjected to the “misinterpretation and twisting of lyrics.”

The crux of the campaign focused on two songs, “Djin” and “Idols.” Both featuring a play on words (Djin, the demon, interchanges with gin, the drink) and draw on biblical and pagan themes.

During a 2016 NPR Tiny Desk Concert, Sinno explained the meaning of “Djin.” He said: “It draws comparisons between Christian mythology and Dionysian mythology. But it’s also about getting, like, really messed up at a bar.”

The band’s defenders say the meaning of the words are open to interpretation, and accuse detractors of nitpicking lyrics.

They also point out that since the release of the two songs in 2015, the band has performed in multiple Lebanese venues, including Byblos, in 2016, and the mountain town of Ehden, considered a bastion of Christianity in the country.

“It is important to us that we clarify that we have been performing these two songs in Lebanon since 2015 without objections,” the band statement read.

“Even though the investigation concluded we hadn’t committed any criminal offenses, the attack and threats kept growing. Very few listened, and often we were not allowed to speak for ourselves,” the band said in the statement.

As the movement against Mashrou’ Leila picked up steam, detractors highlighted Sinno’s sexuality to disparage the band further.

The band received death threats. But instead of being given protection from the state, the group said they were called in for questioning by security forces “for the first time the band’s history.”

Right-wing Christian mobilizing

For analysts and activists following Lebanon’s political developments, the Mashrou’ Leila case is another step in the rise of a new kind of right-wing Christian populism. Experts say it mirrors the growth of right-wing movements elsewhere, especially in the ways that adherents find common cause on issues about identity, whether LGTQ status or national origin.

In recent months, the country’s main Christian parties, namely the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) and the Lebanese Forces, have spearheaded calls for a crackdown on Syrian refugees and undocumented Syrian workers. Last month, Labor Minister Camille Abousleiman, who is Christian, introduced new work restrictions for largely impoverished Palestinian refugees, prompting hundreds of people to take to the street across Lebanon in protest.

In 2017, Lebanon’s Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, who also leads the FPM, embraced the label his critics gave him and declared himself a “racist Lebanese.” He has been a strong supporter of a government push to repatriate the country’s Syrian refugees.

“Because we love the Syrian people, we are calling for their return to their country. Because we are Lebanese who love the Lebanese people we are calling on the Syrian people to return to their country,” said Bassil during a televised speech. “And (it’s) because we are racist Lebanese … yes, we are racist Lebanese.”

Lebanon has hosted over a million Syrian refugees since an uprising-turned-civil war rocked the neighboring country.

Some of the right-wing Christian activists who spearheaded the campaign against Mashrou’ Leila identify as political activists in Bassil’s party, which was founded by Lebanon’s President Michel Aoun.

Read more: Why Lebanon is gearing up for a record number of tourists

“This is a direct threat … to all who participate in promoting the performance in Byblos,” FPM activist and plastic surgeon Naji Hayek said in a Facebook post that was later taken down. “The concert will be stopped by force and not by our wishes alone, he said.

In an interview with CNN, Hayek identified himself as one of the initiators of the campaign to shut down Mashrou’ Leila’s performance, but insisted that his methods were “non-violent.” He said the group threatening to stop the concert planned to “throw tomatoes” at the concert, and to close roads leading to it.

The activist said the two songs at the center of the controversy expressed a “clear insult” to Christianity.

“Any attack on our religion will trigger a reaction,” said Hayek.

Asked why the campaign against the band began roughly four years after the release of the songs, Hayek said he had just discovered it. “The song was sent to me by a priest,” he said. “People didn’t know. Now people know.”

FPM officials said activists affiliated to the party, such as Hayek, express “personal opinions” and not that of the party.

“The FPM has not taken any stance on this musical project,” Bassil’s communications advisor Antoine Constantine told CNN. “We are with the freedoms afforded by the constitution and laws of Lebanon and, of course, we oppose anything that touches the symbols and sensitivities of any religion under the guise of freedom of expression.”

But human rights activists say this campaign is acting with impunity provided by Lebanon’s powerful parties.

“There is a general ambience in the country of right-wing fascism, so there’s fertile ground for going after people for whatever reason related to religion,” said Rima Majed, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the American University of Beirut.

“This is a good target. They’re Lebanese. They’re queer,” Majed added. “If Madonna were performing, no one was going to say anything. But if it’s Mashrou’ Leila, it’s an easier target.”

“There’s an unprecedented level of acknowledging things that previously were unacceptable,” said Majed. “When (Bassil) said ‘I’m a racist’ he said it with pride.”

Since the campaign to cancel Mashrou’ Leila’s concert began, rights groups have organized street protests and created Facebook groups to condemn attempts to silence the band.

Lawyer and human rights activist Khaled Merheb told CNN he had seen messages posted to WhatsApp groups in which participants were talking about how they were going to “destroy everyone who was going to the concert. And they were showing weapons, like guns,” he added.

Merheb was invited to the WhatsApp group used to organize against the concert and took screenshots, that CNN has seen, to build a case against the Christian activists. Merheb has filed a lawsuit against some members of the campaign.

The outcome of the lawsuit is not yet clear, but rights groups and activists say they see the Mashrou’ Leila case as key to their bid to defending human rights in the country.

“This is a threat to all of us. It means that all of our rights are in danger,” said lawyer Saghieh.

“This is not about the band. It is through this band and through this discourse that we discover how weak Lebanon is, how violent and how intolerant.”