Fears are growing among India’s 200 million Muslims that they could soon be classified as illegal immigrants under new, far-reaching government proposals.

Earlier this year, authorities released an updated count of Indian nationals in the northeastern state of Assam, home to more than 30 million people.

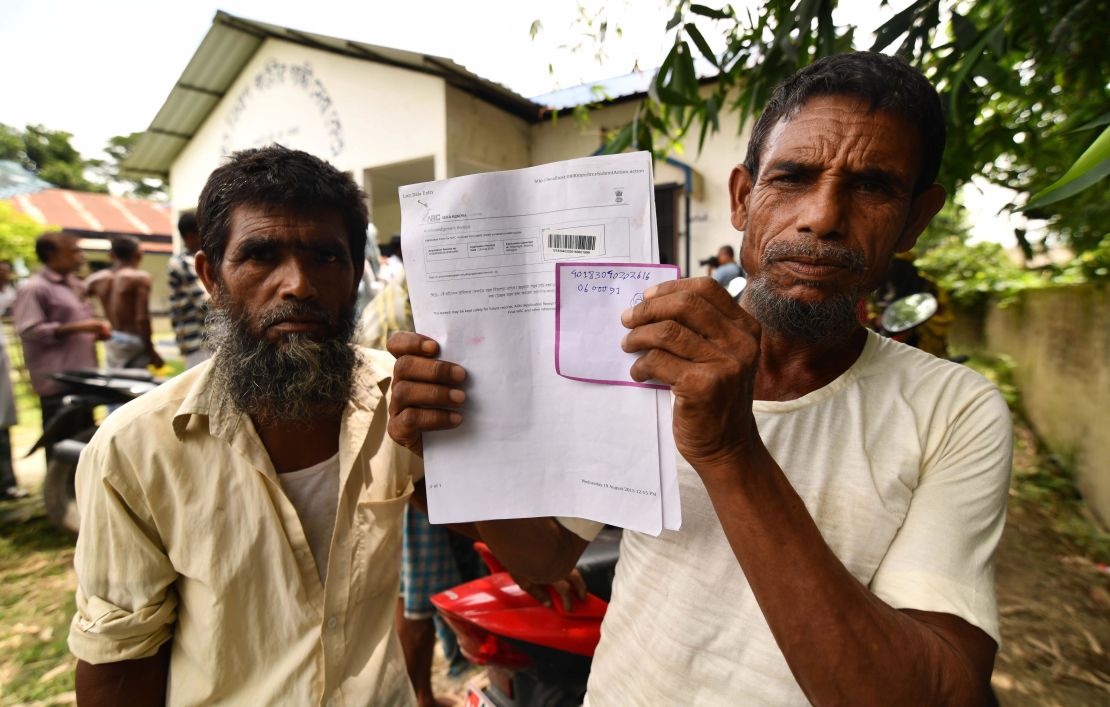

In order to make it onto the registry, residents had to provide the government with evidence that their families had migrated to India before March 24, 1971, around the start of the Bangladesh war of independence.

A little over 1.9 million people didn’t have the right documents.

By any measure, 1.9 million is a large number, but it wasn’t enough for those who had demanded the identification of undocumented people.

For years, Hindu nationalists have alleged that millions of Bangladeshi economic migrants are living and working illegally in India. The issue has been a constant source of political tension in the Indian states bordering Bangladesh – including Assam. Updating the 1951 National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam was considered a means of identifying these illegal immigrants.

Throughout the identification process, critics contended that the registry would lead to the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Bengali-speaking Muslims living in Assam, who’d been there for generations but just couldn’t prove it.

The NRC, however, showed that it wasn’t only Bengali-speaking Muslims who were living in Assam without the required documents – many Hindus of different ethnicities were also left off the list.

Their exclusion frustrated many in Assam’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, who attempted to undermine the legitimacy of the registry by saying it had had left out “some genuine Indian citizens.”

The BJP, which also rules India’s federal government and is headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has now solved this apparent problem.

The Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB), which was passed by the country’s Parliament, allows any legal or illegal immigrant of Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, Christian or Parsi faith, who came into India from Pakistan, Bangladesh or Afghanistan before 31 December 2014, to become Indian citizens.

The only major religion this amendment leaves out is Islam. The government’s justification is that Muslims are in a majority in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, and it is the non-Muslims who face religious persecution in those countries.

“Not one (Hindu) refugee will have to leave. And we will not allow even one infiltrator to stay back,” declared India’s powerful Home Minister Amit Shah, Modi’s closest aide in October.

With dog-whistle politics, Muslims are being branded “infiltrators” and non-Muslim immigrants are being labeled refugees fleeing religious persecution, even if they weren’t. This division has been formalized through the new citizenship law.

Of the 1.9 million people in Assam whose citizenship is in doubt, everyone except Muslims can now be treated as Indian citizens.

Shah has promised to replicate the Assam registry exercise across India, starting as early as next year. If implemented, the National Register for Citizens will ask 1.3 billion people to prove their citizenship.

Given Shah’s repeated promise to eject “infiltrators” before the next general election in 2024, the concept of deporting or locking people up does not seem to be mere political rhetoric. His has made his views about “illegal immigrants” clear. In May, he described them as “termites.”

Meanwhile, Modi said Congress and other opposition groups were spreading “lies and more lies” about the citizenship law, adding it is “in line with our ethos of assimilation and compassion, it ensures a better life for persecuted minorities from other nations.”

For many months now, the 200 million or so Muslims across India have quietly been preparing for the NRC, putting together their documents to show they’ve been living in the country for generations.

Through religious institutions and WhatsApp groups, they’ve been figuring out which documents might save them from being classified as illegal immigrants: inheritance records, birth certificates, refugee registration documents, and so on.

According to Aman Wadud, a lawyer who has been working with Muslims who have been declared illegal immigrants in Assam, the NRC process is punishment in itself.

“It has taken a huge toll on people’s financial condition to run around arranging documents, getting them verified, traveling hundreds of kilometers for hearings before NRC authorities,” says Wadud. “Anyone could file an objection against another individual, resulting in more documents, verification, and hearings.”

Of particular focus for the BJP is the state of West Bengal which borders Bangladesh. More than a quarter of the state’s population of 90 million people are Muslim. The BJP has never won the state election, but hopes to do so in 2021. The NRC will likely hang over that election – and polarize voters along religious lines.

“Indian Muslims are extremely apprehensive about the intentions of the Modi government with regard to CAB and NRC,” says Shahid Siddiqui, a Muslim community leader and editor of an Urdu-language newspaper. “Muslims can see that ultimately it is they who are the target of this meaningless exercise. We should all adopt the Gandhian way of non-cooperation against the NRC.”