In the months since Congress has tried to respond to the coronavirus outbreak, the two most powerful players in the Senate have rarely engaged directly in talks with one another about the legislative response – instead, often trading openly hostile barbs during this high-stakes election year.

And as Washington now struggles with its biggest challenge in its response so far, with the two parties at sharp odds over the next phase of its response and with millions waiting for an extension of expired jobless benefits assistance, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer have yet to sit down to see if they can cut a deal that can achieve the 60 votes needed in the deeply divided body.

The talks, instead, have been led by senior Trump administration officials, who are sitting down behind closed doors with Schumer, a New York Democrat, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a California Democrat, and later briefing McConnell, a Kentucky Republican, about the negotiations as they seek his guidance and counsel.

“We’re going to brief Mitch McConnell and then we will make some comments,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told reporters Monday as he and White House chief of staff Mark Meadows left Pelosi’s Capitol suite after a two-hour meeting with the speaker and Schumer.

The previous four legislative packages followed a similar pattern: Mnuchin engaged in shuttle diplomacy, meeting with Democratic leaders first and then with McConnell, who shared his input, which was then delivered back to the Democrats. Those measures ultimately sailed through Congress given the widespread support for an aggressive response from Washington.

But this time, with just three months until Election Day, Republicans are clashing with Democrats about the scale, scope and details of any new relief package – and the GOP itself is badly divided about whether anything is needed at all.

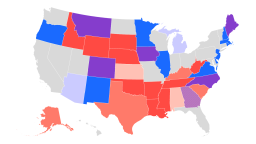

And what’s missing so far from the talks: McConnell and Schumer sitting down to try to reach a deal to see if their respective caucuses could coalesce behind any package as the pandemic continues to paralyze the country. And it comes at a time when Schumer and McConnell are leading their parties in a furious battle across the country for control of the chamber, with the New York Democrat pining for the majority leader title that McConnell has held since after the 2014 midterms.

“It’s awful,” said Sen. Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, when asked about Schumer and McConnell not engaging in directly in negotiations now.

“The better they get along, the better I like it, and the better we do,” said Tennessee GOP Sen. Lamar Alexander, a close McConnell ally.

McConnell and Schumer have long had a competitive and at-times frosty relationship, something that stems back to Congress’ passage of the bank bailout of 2008, which was approved during another highly contentious election year and in the middle of another economic crisis.

And since Schumer became Democratic leader in 2017 at the same time that Donald Trump became President, the chamber has spent most of its time confirming presidential nominees rather than as a body designed to achieve consensus on pressing policy matters, meaning the two have spent less time negotiating over moving legislation on the floor, something necessary in a body where consensus is crucial to passing bills.

“Ask him,” Schumer told CNN on Monday when asked why he hasn’t been negotiating directly, one-on-one, with McConnell.

Asked to characterize his relationship with McConnell, Schumer only said: “Look, he is the Senate leader, but he’s not in the room. And it’s hard to negotiate with someone who’s not in the room.”

Schumer declined to comment further. “That’s all I’ll say,” he said.

In a brief interview last week, McConnell downplayed any rift in his relationship with Schumer.

“Oh, I think it’s fine,” McConnell told CNN when asked about their relationship. “We haven’t been able to have any real meetings lately, but it’s nothing personal in this.”

Asked why the two of them aren’t trying to cut a deal, McConnell said: “Because you need the guy with the pen. You cannot make a deal unless you have the President involved. So the two power-centers on legislation are the President and the Democratic majority in the House and a substantial Democratic minority in the Senate.”

McConnell added: “So, ultimately the only way we can get this together is for them to reach an agreement. I’m fully aware of what’s going on, but I can’t deliver the pen.”

On the floor, the rhetoric between the two men has been heated – and at times personal.

While negotiations were underway in Pelosi’s office Monday with Meadows, Mnuchin and Schumer – in their sixth day of face-to-face talks – McConnell went to the Senate floor where he blasted the Democratic leaders, accusing them of stalling negotiations and demanding their “massive wish list” be included in the bill.

“The speaker of the House and the Democratic leader continued to say our way or the highway with a massive wish list,” McConnell argued. “The Democratic leaders insist publicly they want an outcome, but they work alone behind closed doors to ensure a bipartisan agreement is actually not reached.”

An angry Schumer responded moments later, when he accused McConnell of giving “partisan speeches” while congressional Democrats and the White House were trying to cut a deal.

“Leader McConnell is busy giving partisan speeches, while, for the last two-and-a-half hours, Speaker Pelosi, myself, Secretary of Treasury Mnuchin, and chief of staff Meadows were sitting in a room, working hard, trying to narrow our differences and come to an agreement,” Schumer said.

Both sides blame the other for breakdown

Senate leaders didn’t always have such frosty relations – even during the most polarized of times. Ahead of Bill Clinton’s Senate impeachment trial in 1999, for instance, then Senate GOP Leader Trent Lott and Senate Democratic Leader Tom Daschle cut a deal governing the rules of the proceedings, which was approved 100-0 in the body. Ahead of Trump’s 2020 impeachment trial, talks between McConnell and Schumer quickly broke down over the rules of the proceedings, which the GOP leader pushed through on a party-line vote after days of public battling.

Don Ritchie, a former Senate historian who worked in the Senate’s historical office for roughly 40 years, said the breakdown in large part is due to the change in makeup of the Senate caucuses – which have fewer moderate members and more ideological rigidity on both sides.

“They lead entirely different parties, and as a result, they aren’t constantly trying to win over other people’s support. Everything is us vs. them. There is not a lot of middle ground at all,” Ritchie said.

Both sides now blame the other for the breakdown between the two leaders and the problems within the Senate.

Democrats point to their repeated demands for McConnell to begin talks with them soon after House Democrats passed their $3 trillion relief package more than two months ago. McConnell instead said that Congress needed to assess where the next phase of stimulus was needed and first oversee the implementation of the $3 trillion approved earlier this year.

“It’s the sorry state of affairs here,” Senate Minority Whip Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, said when asked why the two leaders aren’t talking. “It’s just Sen. McConnell is not communicating with Schumer, and going his own way. I mean he’s tries to do everything in his office. That we know that will never work.”

But the GOP says it’s Schumer who can’t be trusted, arguing he’s made finding bipartisan consensus harder and have accused him of holding back some of his members who may be more willing to get behind the GOP approach. While Democrats say that McConnell has tried to jam them over legislation – rather than seek their input – Republicans argue that Schumer has rallied his caucus to oppose even measures that came as a result of bipartisan talks, such as the Republicans’ first version of the March stimulus law known as the CARES Act.

Plus Republicans were angry last week when Schumer blocked efforts for a one-week extension of expiring jobless benefits at $600 per week, something the Democratic leader contended fell far short of what’s needed.

“That’s not his reputation within the conference,” Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri said when asked if Republicans find Schumer trustworthy.

“The leader’s the better judge of that and when its fruitful and not fruitful” to negotiate with Schumer, Hawley added. “I’m sure that Sen. Schumer is working every political advantage here. Not surprising.”

After Schumer and Senate Democrats blocked the initial GOP version of the CARES Act, Schumer, Mnuchin and a top White House official, Eric Ueland, engaged in marathon negotiations for days – with the administration officials walking the stone’s throw from Schumer’s office to McConnell’s nearby suite that’s just around the corner on the second floor in the Senate. McConnell would give his input, and Mnuchin and Ueland would brief Schumer, a pattern that continued during seemingly round-the-clock talks. Ultimately, a deal was reached and was approved in the Senate without a dissenting vote.

Staff for McConnell and Schumer did engage in discussions over the stimulus bill, sources said, negotiating a number of the provisions in the final legislation, and were directly engaged in negotiations over a massive spending bill to keep the government open. But the two leaders spoke sparingly with each other before the March passage of the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill, the largest rescue package in American history.

A similar pattern occurred in April. After Schumer blocked McConnell’s effort to pass a $250 billion increase to the popular small business loan program, the Senate Democratic leader and Pelosi engaged in days of talks with the administration – and cut a deal with McConnell’s blessing and input – worth $484 billion.

Afterward, Republicans began to push back against the staggering amount of spending. So McConnell let his GOP conference air out its differences behind closed doors since May – and later sought to achieve consensus with his own members on the Republican alternative to the Democratic $3 trillion bill, ignoring Democratic demands to begin a new round of talks immediately.

After multiple weeks of talks with Meadows and Mnuchin, McConnell rolled out a $1 trillion plan meant to serve as an opening Republican offer, though a number of his GOP colleagues criticized the proposal and Trump wouldn’t say if he endorsed it.

GOP watches anxiously as administration leads talks with Democrats

Some of McConnell’s own colleagues are nervous about letting Meadows and Mnuchin lead the talks.

“I think it’s concerning that we don’t have any idea really what’s going on,” Hawley said Monday. “I think a lot of senators have that sentiment.”

Sen. John Kennedy, a Louisiana Republican, said the problems in the Senate are “deeper” because the body takes up so few pieces of legislation where the narrowly divided body would have to work together to find common ground.

“I wish they would talk, but I think it’s deeper than that,” Kennedy said when asked about McConnell and Schumer. “Tell me that there was a time that we actually legislated, and we debated, and we offered amendments, and we considered – sometimes reconsider – our assumptions after hearing the arguments of people who disagree with us.”

The tense relations in the body have indeed been years in the making.

Durbin, who was also the No. 2 under the previous Democratic leader, Harry Reid of Nevada, said things were different between the Nevada Democrat and McConnell – even as those two battled frequently in tense arguments for years.

“There was more communication at that time. The situation is worse now,” Durbin said, pointing to a breakdown after McConnell’s move to keep vacant a Supreme Court seat and refuse to move forward with confirmation proceedings for then-President Barack Obama’s pick of Merrick Garland in 2016. “Once McConnell got on this, hellbent to fill every judgeship at any cost, Merrick Garland, things really went to hell in a hurry.”

But Republicans blame Reid for the rapid decline of relations in the chamber, pointing to his 2013 use of the so-called “nuclear option” that gutted the minority’s party ability to filibuster presidential nominees other than for the Supreme Court. When Trump took office in 2017, McConnell replicated that tactic and effectively killed the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, paving the way for Trump’s two picks to be confirmed largely along party lines rather advance with a super majority of 60 senators.

And if former Vice President Joe Biden wins the White House, Democrats are talking about doing away with the filibuster so a simple majority of senators can approve legislation, something that would have profound ramifications for the body, for a President’s agenda and further roil relations in the chamber.

“I don’t really think that was much different,” said Texas Sen. John Cornyn, a member of McConnell’s leadership team when asked about the GOP leader’s relationship with Schumer versus Reid. “Harry Reid is a very difficult guy. And, Schumer is a little more affable. Harry was just downright nasty.”

McConnell, who is up for reelection in the fall, also was on the ballot in 2008 during the heat of the financial crisis. Weeks before the election, Schumer and McConnell cut a deal along with other party leaders and George W. Bush’s administration on the massive bank bailout, a deeply unpopular measure that helped prop up Wall Street.

Afterward, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, which Schumer ran at the time, aired an ad that bashed McConnell’s bailout vote, something the Kentucky Republican viewed as a breach of a gentlemen’s agreement to avoid using the vote as a campaign attack. Schumer later said he had nothing to do with the ad since he was barred by law from coordinating with the campaign committee’s arm that ran the attack ad. People who know both men said it speaks to their long history of partisan battles.

“Both of them have been at this long time and they know what they need to do in order to accomplish what they want to accomplish,” Cornyn said. “But it’s a turbulent time for everybody.”

CNN’s Ted Barrett, Ian Sloan and Austen Bundy contributed to this report.