Lviv, Ukraine (CNN) — When Serhii woke up to news reports that a bomb had flattened Mariupol’s Drama Theater, where hundreds of people had been sheltering, he couldn’t breathe.

His wife and their two daughters were inside.

A day before the attack, the 56-year-old editor, who lives in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, received a panicked call from his 30-year-old daughter.

He hadn’t heard from her since March 1, when Russian forces intensified their siege of Mariupol, the strategic port city, launching a relentless barrage of rockets and bombs from land, sky and sea.

As electricity and internet service went out, Mariupol was largely cut off from the outside world. Serhii, who asked that only his first name be used for security reasons, waited desperately for any update from his girls.

In its absence, he had little choice but to rely on the grim picture of life and death being relayed by Mariupol officials: Residents were living in “medieval conditions,” forced to melt snow for water and cook food outside on open fires. Civilian targets, including apartment buildings, a maternity hospital and the main administrative building, were reduced to rubble. Ceasefires were ignored and evacuation corridors blocked.

It was a situation that would have been unthinkable a few short weeks ago in the bustling industrial city, once known for its seaside resorts and a major steel plant, and now the scene of fierce fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces.

Serhii worried for his wife, 56, and daughters — especially the eldest, 36, who lives with a disability and needs daily medication. But his relief at finally hearing from them was quickly replaced by a gnawing fear.

In a harried conversation, his youngest told him she had been able to charge her phone at a diesel generator, but that she only had a little time to talk. She explained that their apartment had been destroyed in the shelling, and she wasn’t sure where they would be safe. He told her to go to the Drama Theater, in the city center, where officials were organizing buses to evacuate residents.

“When I advised them to move to the drama theater as an evacuation site, and the next morning I learned that this place was bombed … I almost went crazy, insane,” Serhii told CNN in a phone call from Kyiv. “Because I actually sent them under the bombs.”

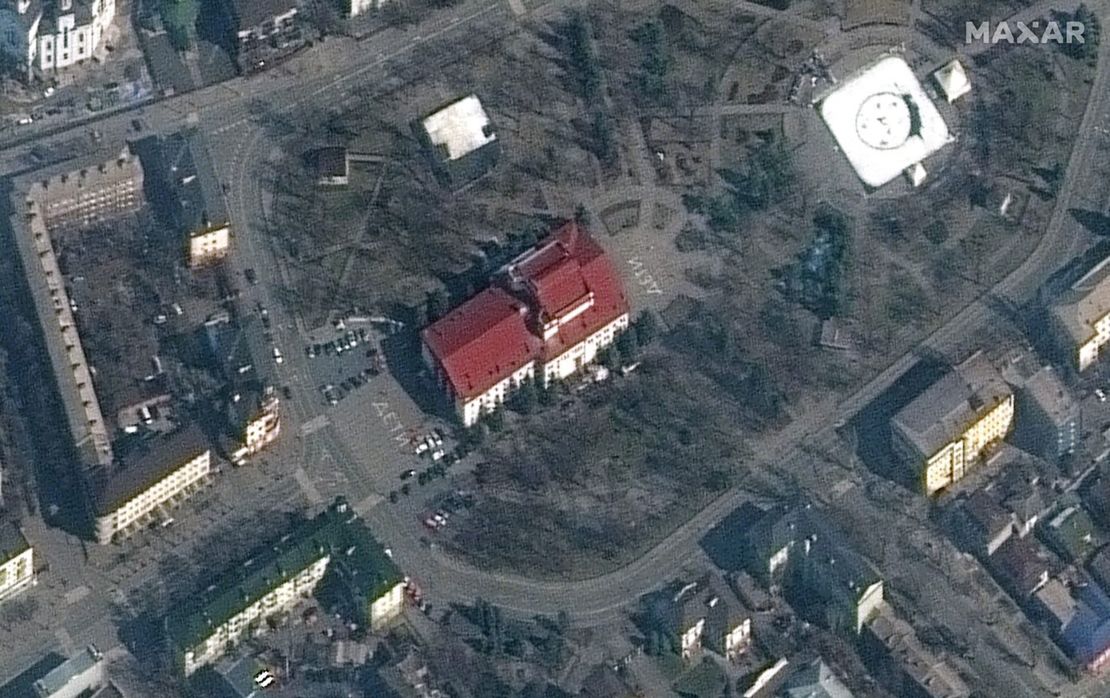

The March 16 bombing of Mariupol’s theater, where Ukrainian officials say an estimated 1,300 had sought refuge, was among the most brazen of Russia’s attacks on civilians since its invasion began in late February. Painted on the ground outside the building — in giant Cyrillic letters — was the word “CHILDREN.” The message — large enough to be viewed from the sky — was scrawled near a public square that, before the war, was busy in summer with kids swinging on a jungle-gym and running through fountains. Russia has denied its forces hit the theater, claiming instead that the Azov battalion, the Ukrainian army’s main presence in Mariupol, blew up the building.

After 24 hours of near-hysteria, wondering if his family was still alive, Serhii’s phone rang. His daughter told him she had left the theater to check on an elderly relative shortly before the bomb struck. She rushed back to find the building cleaved in half, with the central auditorium of 600 to 800 seats completely flattened, and people drenched in blood and white debris beginning to emerge from the rubble. Among them were her sister, who had been hiding in a portion of the theater that did not collapse, and her mother, who was dug out of the bomb shelter along with other survivors.

The three women, carrying nothing but a backpack with their essential documents, managed to catch a ride with six others in a small car, paying the driver all the money they had — 2,000 hryvnia, the equivalent of about $68. She said they got out at a checkpoint manned by Russian soldiers, and walked some 12 miles further on to Melekino, where their neighbors have a dacha, or summer house.

The small village on the Sea of Azov is overflowing with displaced people who have poured in from Mariupol, Serhii’s daughter told him, adding that there was no food or fuel left.

“In Melekino there is a real famine, a holodomor. People in the villages have no supplies, absolutely all shops are closed,” Serhii said, referring to the man-made famine that gripped the Soviet republic of Ukraine in the early 1930s, killing millions. The term is derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger (holod) and extermination (mor).

Unable to travel himself, Serhii is now frantically searching for a driver who will make the dangerous journey to retrieve his wife and daughters from the dacha where they’re camping out. But he hasn’t had any luck yet. It’s a frightening proposition: any volunteer would run the risk of being caught in the crossfire, or being captured by the Russians. Over the last week, Russian forces have been deporting thousands of Mariupol residents against their will to far-flung cities in Russia, according to city officials and witnesses. And on Monday, Moscow called on Mariupol to surrender — a notion Ukraine swiftly shot down.

Serhii’s family’s harrowing escape from Mariupol is among the first stories to surface from survivors of the theater bombing. For days, family and friends of those inside have waited on tenterhooks for news of their fate, posting in local Telegram channels and Facebook groups asking if anyone has seen their loved ones. Posts from some of those who have managed to escape the city haven’t instilled much hope, describing basements turned into tombs, and streets littered with dead bodies.

Petro Andriushchenko, an adviser to Mariupol’s mayor, told CNN on Sunday that the battle for the city has made it impossible to retrieve and identify the dead, or treat the wounded. “We cannot carry out rescue operations in the current conditions: Street fighting, shelling, bombing are going on,” he said of the theater attack, adding that many of the estimated 200 survivors are now in other shelters, or in the process of being evacuated to Zaporizhzhia, a city on the Dnieper River about 140 miles away.

On Sunday, another strike hit an art school in the city, where Andriushchenko said 400 people were believed to be sheltering. But with fierce fighting and communications down, it has been difficult to get a clear sense of the loss of life there.

In a video message posted to Facebook in the early hours of Sunday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said the siege of Mariupol would go down in history as a war crime. “To do this to a peaceful city … is a terror that will be remembered for centuries to come,” he added.

But like the other cities and towns dotted across Ukraine’s east and south which are now being strangled by Russian troops, Mariupol has become a black box, with information only beginning to trickle out as residents escape.

‘I realized that I could wait no longer.’ We had to leave.

After the maternity hospital near Anna Kotelnikova’s home was hit on March 9, sending pregnant mothers scrambling through the ruins clutching their bellies, she decided to move to her parents’ apartment six miles south, in a block overlooking the Drama Theater.

Kotelnikova, a 36-year-old anaesthesiologist, has volunteered as a medic for the Ukrainian army since the spring of 2014, when Russia-backed separatists attacked Mariupol; separatist forces held the city for a month before the Ukrainian government wrested back control. Because of her involvement in the conflict, Kotelnikova was strongly advised to leave Mariupol when Russia invaded Ukraine last month. She refused, unable to conceive of the carnage that was in store for her beloved hometown.

But as the bombing worsened, the barrage increasingly unpredictable and indiscriminate, she began to change her mind. On the night of March 14, sheltering with her sister, brother-in-law, nephew and her parents — who are in their 80s and lived through Mariupol’s occupation by Nazi Germany — she knew they had to leave.

“Every day we heard explosions approaching, bombing. That night was just awful. From midnight until the morning … The bombing did not stop,” she told CNN in a call. “When it was possible to open the curtain … I saw that everything in the direction of my house was in black smoke.”

“I realized that I could wait no longer,” she said.

Across the square from her parents’ apartment, locals and city officials were organizing evacuations at the Drama Theater. Inside, the situation was dire, Kateryna Erskaya, a journalist who had been delivering aid to the site, told CNN.

More than a thousand people were camped out inside the unheated building, trying to keep warm in freezing conditions with cardboard boxes, blankets and near constant fires, she said. The blazes, fueled by bits of destroyed homes and tree branches, were used to cook any food people could find. Most people’s phones were dead and mobile signals were rare — their only sense of the outside world coming from the roars of planes overhead and the noise of skirmishes nearby.

“This sound of combat was a constant soundtrack,” said Erskaya. On March 16, just hours before the attack, she managed to flee the city.

Kotelnikova did the same a day earlier, on March 15. She sprinted from her parent’s apartment to the theater, confirmed that a convoy of more than 200 cars was leaving at 9 a.m. and snapped some photos of the “CHILDREN” sign scrawled on the ground, before running home to tell her family to pack. Within an hour, they were out the door.

Following advice from friends, she said she wiped her phone, scrubbing it of messages, applications and photos — anything that might give Russian soldiers cause to detain her at a checkpoint on the way out of the city, something that city officials and eyewitnesses say has been happening to activists and volunteers like her.

They made it through each stop, slowly navigating the road north to Dnipro, in central Ukraine. The drive, which normally takes nine hours, took two days. They stopped in fields when dusk fell, staying on the road to avoid mines and huddling to keep warm as temperatures dropped to -11 degrees Celsius (12 degrees Fahrenheit).

Kotelnikova said that when the group got to Zaporizhia she was overwhelmed with relief. “I was ready to just get on my knees and kiss the ground.”

Others haven’t been as lucky.

Julia Paevska, also known as “Taira,” a storied Ukrainian military medic known for her bravery and compassion, was captured by Russian forces in Mariupol earlier this month, according to local officials. Andriushchenko, an adviser to Mariupol’s mayor, said Taira was among a number of activists, law enforcement officers, army veterans and volunteers who have been kidnapped by the Russians. US ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield said on Sunday the reports were “disturbing” and “unconscionable” if true.

“They fall, as we say, ‘in the basement,’” Andriushchenko said, referring to those who have been taken by the Russians. “On the one hand, the Russians are simply trying to discredit any sense of possible Ukrainian resistance. At the same time, it is an act of punishment for the war of 2014 to 2015.”

Taira, who was an Aikido marial arts instructor before she volunteered as a medic, was profiled in an award-winning book, by conflict reporter Yevgeniya Podobna, about 25 women who joined the armed forces in 2014. In a 2018 interview, she speculated about what might happen after the war: “We’ll see. Maybe I’ll be a coach. Maybe I’ll be growing roses in a garden. Maybe I’ll find another war and go there to save people.”

In addition to those who have disappeared, like Taira, Mariupol officials say others have been forcibly deported to Russia. Officials are trying to track their whereabouts through eyewitness accounts, direct messages and some sympathetic Russians who oppose the war in Ukraine, Andriushchenko said.

“People who have already been deported are in touch with us. That’s why we know which cities people are deported to and how it happens. Even when people have their phones and SIM cards taken away, they find an opportunity to get in touch with us,” said Andriushchenko, whose days are now spent fielding a stream of calls and messages from Mariupol residents trying to track down their relatives. His main mission, he told CNN, is to get people out safely and reconnect them with their loved ones.

On Monday morning, Ukraine’s government rejected Russia’s calls for Ukrainian forces in Mariupol to lay down their weapons in exchange for “safe passage” out of the city. It is an ultimatum that Russian President Vladimir Putin has used elsewhere — in Grozny, when the Russian republic of Chechnya rebelled in the 1990s, and in Aleppo, where Moscow helped quash a popular uprising against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in 2015. At the blunt end of the ultimatum: Civilians left inside the city, either trapped or too scared to flee, who face a “military tribunal” and Russia’s wrath.

For those still anxiously awaiting news of friends and family stuck in Mariupol, it is a terrifying new development.

Even though his girls have been able to leave the city, Serhii won’t be able to rest until they’re reunited. Still, he said, it was a miracle that they survived.

“The destruction now is greater than the Nazis did during World War II,” Serhii said. “This is a historical remake, this is another war crime.”

Olga Voitovych, Oleksandr Fylyppov and Dmytro Olenschenko contributed to this report.