Beth Pratt first explored the wonders of Yellowstone National Park through the pages of a book.

Inside a tattered hardcover entitled “National Parks of the U.S.A.,” she still has a list where she penned in five Western parks she dreamed of visiting. Among the quintet was Yellowstone.

“I can still remember gazing endlessly at the photographs of granite peaks, roaring waterfalls and magnificent wildlife, and daydreaming about wandering in those landscapes. I would think ‘someday, someday …’” she told CNN Travel.

Her someday came during a cross-country trip from her Massachusetts home to California. As for her first look at Yellowstone, “it was truly a moment of awe.”

Pratt, who later took a job at the park, shared an entry from her journal dated September 20, 1991:

“Yellowstone is beautiful. No description I could give would do it justice – I am no John Muir. It is enchanting and full of natural wonders and the wildlife are everywhere. A Disneyland for naturalists. Right now, I’m watching a herd of elk across from my campsite. The bull sings to his herd an eerie song, yet a sound suited to the land.”

Indeed, Yellowstone is a land rich in dates and memories.

The park – 96% of which is in Wyoming, 3% in Montana and 1% in Idaho – is celebrating a major milestone this year.

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act into law. With the stroke of his pen, he created the first national park in the United States but also the world.

On this 150th anniversary, the National Park Service and Yellowstone fans look at the past, present and future with events planned well into the year.

A very short account of a very long history

Yellowstone’s history actually begins way before 1872, and it wasn’t as untouched as many people might think. For thousand of years, we have evidence of people thriving on the land’s bounty.

“Some of the modern trails frequented by hikers in Yellowstone are believed to be relics of Indigenous corridors dating all the way back to roughly 12,000 years ago,” the US Geological Survey says.

It was familiar ground to Blackfeet, Cayuse, Coeur d’Alene, Kiowa, Nez Perce, Shoshone and other tribes – all believed to have explored and used the land here, the USGS says.

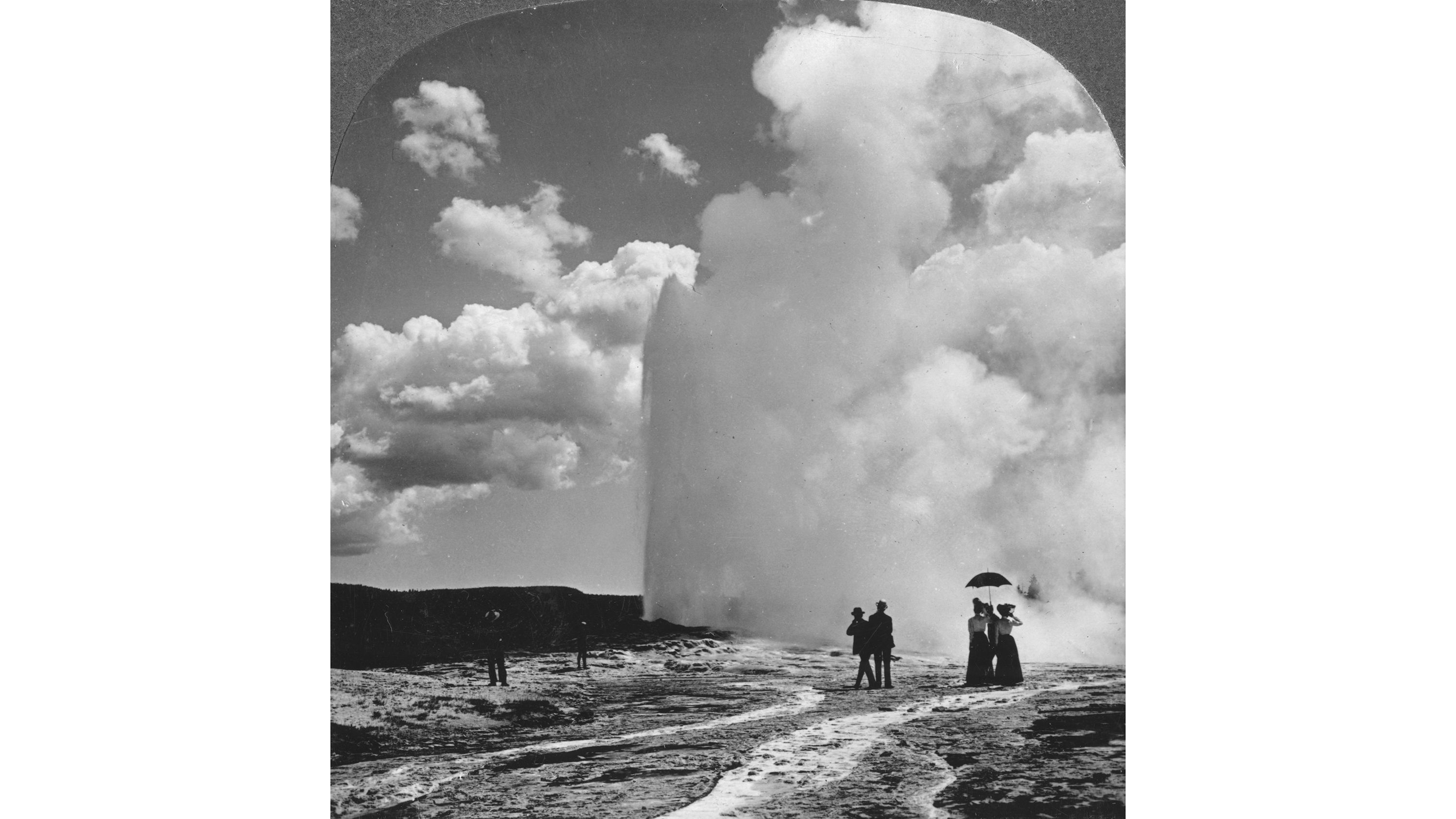

They “hunted, fished, gathered plants, quarried obsidian and used the thermal waters for religious and medicinal purposes, the NPS says. (Yellowstone sits atop a supervolcano, and it has the world’s greatest concentration of geysers as well as hot springs, steam vents and mudpots, the NPS says.)

While the Indigenous people lived in balance with the land, waves of westward US expansion began putting pressure on wilderness areas throughout the West.

European Americans began exploring the area that’s now Yellowstone in the early 1800s, according to the NPS, and the first organized expedition entered the area in 1870. Vivid reports from the expeditions helped persuade Congress – whose members hadn’t even seen it – to protect the land from private development.

Just two years later, Yellowstone was officially created.

Significance of Yellowstone ‘cannot be overstated’

The creation of Yellowstone was a game changer and a trendsetter.

It helped usher in more US national parks, with California’s Sequoia and Yosemite joining the roster in 1890. Mount Rainier was added to the list in 1899. Today, there are 63 national parks, with the newest being New River Gorge in December 2020.

Ken Burns titled his 2009 documentary on US national parks “America’s Best Idea.” Its value has made it a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“The significance of Yellowstone to wildlife conservation and preserving our wild heritage cannot be overstated,” said Pratt, who is currently California regional executive director for the National Wildlife Federation.

She said the formation of the park ensured “that our natural heritage is held in trust for future generations” and “inspired other public land protections like the open space movement – so the legacy of Yellowstone for the common good extends far beyond even the national park system.

“Yellowstone National Park also serves as a time capsule, a sort of ‘land that time forgot’ in terms of wildlife. It’s one of the few places you can get a sense of a past when wildlife dominated our world,” Pratt said via email.

‘Part of something bigger’

Jenny Golding is a writer, photographer and founding editor of A Yellowstone Life, a website dedicated to helping people connect with the park. She runs it with her husband George Bumann, a sculptor and naturalist.

They told CNN Travel in an email interview that “Yellowstone has always set the example for preservation and conservation, and balancing those goals with visitation and education.”

“The significance of the park has changed over time, but in recent history it has shown us the critical role of wild places in contemporary life,” Bumann said.

“The park has been a global leader in establishing the range of possibilities and approaches to caring for wild animals and landscapes. It’s also a place for us to find our collective and individual center. People come here expecting to be transformed, or enlightened, in ways they don’t in other places.”

Golding concurs. “You can’t help but be a part of something bigger here,” she said.

“We live and breathe Yellowstone; it’s in the very fiber of our being – the wilderness, the animals, the smell of hot springs in the air. For us, Yellowstone means so many things – wildness, presence and connection with something deep and intangible.”

Mistakes were made

Running the park has been a 150-year learning experience, to put it mildly.

Yellowstone has an uneven history in environmental management and consideration of the Indigenous peoples’ historical ties to the area, said Superintendent Cameron Sholly in an online presentation earlier this year.

“If we rewind to 1872 … we didn’t have a very good track record of resource conservation in the country. It was basically nonexistent,” Sholly said. “Once Yellowstone became a park in 1872, the small group trying to protect it had a really tough time, initially.”

And mistakes were made all along the way, Sholly said.

“We didn’t get it right in many ways. Our government policies were generally to rid the park of predators, and we did that. We did it in mass.” He noted that wolves and cougars were completely rooted out, and the bear population was decreased significantly.

“Beyond predators, we decimated the bison population from tens of thousands in the park to less than 25 animals, and we basically tinkered with the ecosystem and took it completely out of balance, really unknowingly at that point in time.” Sholly said. “Even if you fast forward to the 1960s, we were feeding bears out of garbage dumps so visitors could see them.”

Since then, there’s been a turnaround in attitudes and wildlife.

“So although we’re talking about 150 years of Yellowstone … most of the success of us putting the pieces back together of this ecosystem have occurred largely over the last 50 to 60 years.”

He cited the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone in 1995, which “remains probably the single largest successful conservation effort in the history of this country, if not the world.”

Honoring a long legacy

Sholly also acknowledged work remains regarding Indigenous people.

“We’re putting a heavy emphasis in this area in the fact that many tribes were here thousands of years before Yellowstone became a park.”

He noted the transfer of 28 Yellowstone bison into the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes’ Fort Peck Indian Reservation “as part of an ongoing effort to move live bison from Yellowstone to tribal nations” and upcoming efforts to educate visitors about the park’s long Indigenous history.

“We also want to use this anniversary to do a better job of fully recognizing many American Indian nations that lived in this area for thousands of years prior to Yellowstone becoming a park.”

And even more challenges loom on the 150th anniversary. Yellowstone has invasive species such as lake trout and is affected by climate change. Yellowstone and other popular parks are figuring out how to best handle record crowds. And the park must continue to cope with fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Anniversary events

Because of the pandemic, the park isn’t planning any large-scale, in-person events for now. But it is holding virtual programs and some smaller in-person programs.

Some of the highlights:

• Badges: This summer, the park’s Junior Ranger Program is free of charge. You can go to a park visitor center or information station to get a booklet and earn a badge during your visit.

• Lodging history: Yellowstone National Park Lodges will host a public event at the Old Faithful Inn on May 6, coinciding with the seasonal opening of the historic inn. A Native American art exhibition and marketplace will be open May 6-8.

• Tribal Heritage Center: From May to September 2022, visitors can go to the Tribal Heritage Center at Old Faithful. There, Native American artists and scholars can directly engage with visitors, who will learn how the tribes envision their presence in the park now and in the future.

• Horses: From July 28 to 30, members of the Nez Perce Appaloosa Horse Club will ride a section of the Nez Perce Trail, hold a parade in traditional regalia and conduct trail rides.

• Symposium: The University of Wyoming’s 150th Anniversary of Yellowstone Symposium is scheduled for May 19-20, both virtually and in-person at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. Free registration is required.

Click here to get for the full listing of currently planned events.

Favorite spots in Yellowstone

With the 150th anniversary approaching, Jenny Golding of A Yellowstone Life reflected on her time at the park.

“I first came to the park on a coyote research study in 1997. George [Bumann] and I came back on our honeymoon, and then returned permanently in 2002,” she said. “I had done a lot of hiking and traveling before Yellowstone, but there was no place that touched my soul the way Yellowstone did. Yellowstone has a living, breathing heart.”

They’ve lived there permanently since 2002, “initially working with the park’s nonprofit education partner and now independently.”

As for a special place in the park, Bumann loves Lamar Valley, which is noted for its easy viewing of large numbers of animals.

“It’s a place where you see the Earth for what it has come to be over the course of millions of years, not for the things we’ve done to it. But every time I go out, I find new special things in different places in the park.”

Beth Pratt, who lived and worked at Yellowstone from 2007 to 2011 overseeing sustainability projects, had a hard time narrowing down to a favorite place.

But when pressed, the author of “When Mountain Lions Are Neighbors” said, “I have to give my favorite place in Yellowstone to Norris Geyser Basin. Old Faithful gets all the attention, but Norris is full of wonders.

“Norris Geyser Basin is described in the NPS guide as ‘one of the hottest and most dynamic of Yellowstone’s hydrothermal areas.’ But even this description is an understatement – the otherworldly nature of the area simply evokes awe. When you visit the basin, it’s like being transported to another planet.”

And the memories of the animals stay with her.

“I once saw nine different grizzly bears in one day and had almost 40 bighorn sheep wander by me one day as I ate my lunch. Yellowstone is a wildlife immersion experience like no other in our country.”